Is This Deal Getting Worse All The Time?

A lot of working writers write without contracts. They write based on the strength of their client relationships. Provided there is never a problem, this is fine. Most of the time, when you meet a writer who prides himself on working without contracts, he’s also never had a client try to sue him, nor has he been stiffed for a significant amount of money. In the case of most disputes between a writer and his [disgruntled] clients, a contract could prevent the issue by defining the terms — such as, say, what remedies the parties agree to if the client isn’t happy with the output.

A lot of working writers write without contracts. They write based on the strength of their client relationships. Provided there is never a problem, this is fine. Most of the time, when you meet a writer who prides himself on working without contracts, he’s also never had a client try to sue him, nor has he been stiffed for a significant amount of money. In the case of most disputes between a writer and his [disgruntled] clients, a contract could prevent the issue by defining the terms — such as, say, what remedies the parties agree to if the client isn’t happy with the output.

I once worked with a writer who was… well, bad. Let’s call him “Steve,” which is not his name. Steve had written a massive 100,000 word fantasy novel of which he was very proud. It had been edited no less than eight times, he said. He had churned out x-hundred-thousand words of writing, and therefore he was a most excellent writer, he asserted. He paid up front for an editing job from me and turned me loose on his book.

Steve’s writing was bad. It was so bad that it prompted me to recalibrate my estimate of just how truly awful bad writing can be. I struggled through it and made significant changes to Steve’s book. He was happy with the output I sent him and all was well. But then I made a mistake: I sent him a list of helpful suggestions for how to improve his writing. While I wrote the list very gently and diplomatically, I think Steve was offended.

He wrote me back and demanded all of his money back because I didn’t completely rewrite his awful book. I explained to him that I was out my time and effort and, while I would make a good-faith effort to accommodate him (including taking another, free edit pass at the book, or taking more money to completely rewrite it), we could not start negotiations from the standpoint of, “Steve gets everything and Phil gets nothing.” I was willing to give him a partial refund if no resolution could be reached, but I was not willing to fork over every dime I’d been paid, especially since he would have the benefit of the edit work I had done.

Steve responded by threatening to tell the Internet I suck if I did not give him back at least half his money. I started ignoring him then.

A few days later, I got a letter from a lawyer’s office (emailed as a PDF). It said that Steve wanted his money and I should give it to him, or vague legal action might be considered. I had my lawyer call Steve’s lawyer and explain that Steve had engaged in extortion across state lines. Oddly, we never again heard so much as a peep from Steve or his attorneys, nor did Steve tell the Internet I suck anywhere that Giga Alert could see him do it.

A contract would have prevented all this right? Well, yes… and no. You see, just because you do have a contract (and I’m not saying you shouldn’t), don’t think that protects you in all things. Contracts are useful, but they’re not ironclad magical vestments that shield you from all harm. Contracts merely define certain specifics about your working relationship. There are always things that can come up outside the purview of the original agreement — and then you’ll be wondering what the hell to do about it.

I had a contract with a major publisher to produce several novels. That contract seemed like a guarantee of work I was to do and money I was to earn… except that it wasn’t. When the publisher was purchased by another publisher and the business was reorganized, my contract was killed. I was allowed to keep money that was prepaid to me, but I was not to turn in the work for which I was contracted, and I would not be paid for it if I did. The contract was superseded by a change to the business itself. I was not upset; this can and does happen. As a working writer, you’ve got to be aware of it. You can’t control all external factors, which means sometimes, you’ll think you have a guarantee of work, conditions, or payments… and then the rug will be pulled out from under you.

This happened to me just recently. I was performing contract work for a client who decided that, business-wide, all of his contractors would have to be classified as part-time employees — retroactively to the beginning of the year. I was told that I would have to submit to a background check and that my pay, including money already received, would become part-time employee pay (from which taxes were withdrawn) rather than 1099 contractor pay. I was sent a handy link to a background check service (one that, just a few years ago, was punished by the government for incorrectly reporting criminal background check results).

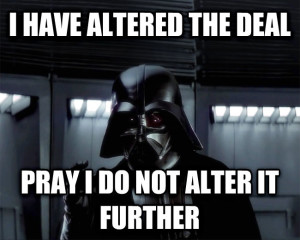

As much as I wanted to keep doing work under contract for this client, this attempt to change the terms of our deal after the fact — to alter the bargain, Darth Vader style — was unacceptable. As a freelancer I am not a part-time employee. I am a 1099 contractor and enjoy the freedoms this confers. I work on my own schedule, I do not submit to background or credit checks, and I answer only to those people with whom my contract is drawn up. There was no way I would be bullied into agreeing to change our contract. I entered into a business agreement with this client under a specific set of assumptions. If those premises change, the deal is off and the work stops.

When people start using the term “retroactively” with respect to a contract you’ve signed, your agreement has become untenable. The only answer to such a demand is a firm, “No.” Never let anyone bully you into changing an agreement… and never believe the fact that you have a contract will stop some clients from trying.

The price for being a working writer is eternal vigilance, which includes a commitment to ongoing business development. Every client is temporary. Some go their own way quietly, while others cut their own throats by trying to change your working agreement. Either way, you must always be looking to replace the business you’ll lose.