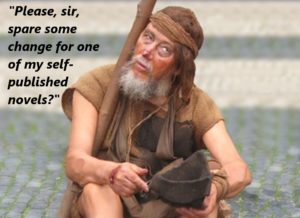

The Etiquette of E-Begging

I saw something recently that turned my stomach. A self-published author who has a considerable following took out an ad on social media to promote his latest work. When one of the targeted audience members complained about being spammed, the author became vulgar and insulting.

I saw something recently that turned my stomach. A self-published author who has a considerable following took out an ad on social media to promote his latest work. When one of the targeted audience members complained about being spammed, the author became vulgar and insulting.

This is a lot like trying to hand someone an advertising flier on a public street and, when they tell you not to bug them, screaming “Well, then F— you, buddy!” at the top of your lungs. Now imagine doing that and then following your victim down the street, pointing and shrieking, “That guy’s a humorless a–hole! THAT GUY’S A HUMORLESS A-HOLE.”

But that’s exactly what the author did.

He had a rancorous exchange with the woman in question, then screen-capped it and shared it with his audience. Mercifully, he blocked out her name so she wouldn’t be subjected to harassment from his fans, but that’s all he got right. An author who behaves this way toward his prospective audience doesn’t deserve to sell a single copy of his book.

Advertising on social media, or soliciting funds at all, is always a delicate proposition. There’s a fine line between asking for support and hectoring people for spare change. Most people refer to such calls for financial support as “e-begging” — and they’re not wrong. The idea is that if you have an audience of sufficient size, they’ll have a vested interest in supporting you financially. They’ll give you money so that you can continue providing them a service. They’ll want to support you because the alternative is not to have you. If you can’t live, you can’t write — and the need to balance paying your bills with writing the next great American novel is a dilemma most authors face.

This is why I draw a distinction between working writers and authors. Anyone can write a novel. It takes no money at all to become an author and even to publish your work on certain platforms. But to make a living from your writing requires a lot more work, a lot more hustle, a lot more late nights… and a fine understanding of the etiquette of e-begging.

Simply put, you cannot afford ever to forget that you are begging people for money when you ask for funds. Whether you do that as part of a crowdfunding campaign, in the form of social media advertising, or in some other solicitation does not matter. However you put the request before the eyes of your audience, you are holding out your hat and hoping they drop some money in it.

Forgetting this leads to arrogance and entitlement. An author who thinks he deserves your money — and that any negative feedback, any nasty comment, any vocal refusal to buy his product, should be met with scorn and derision — deserves to starve. Worse, he deserves to go back to… his day job. If he has the gall to mistreat people who react negatively to his begging, he is saying to you, “I am entitled to your cash.” But he isn’t. No beggar deserves a dollar, spare or otherwise. Asking people for their patronage is always asking for charity.

I can speak from experience. A few months ago I successfully crowdfunded the writing of a parody action novel, Spaceking Superpolice. That novel, which I’m now in the process of editing and laying out for publication, would not exist if not for the charity of my audience. If I choose to take out advertising on social media to sell this book — a sticky proposition at the best of times, because people get testy when they see unwanted posts and commercials in their timelines — I must be on my best behavior. The best response to a negative reaction is either a polite explanation or no response at all. It is never a vicious retort. That’s not just undignified and unprofessional; it’s the kind of thing that should get your social media page shut down. It’s the type of childish response that amateurs make. It is not the conduct of a professional who is worthy of his audience’s hard-earned cash.

I can speak from experience. A few months ago I successfully crowdfunded the writing of a parody action novel, Spaceking Superpolice. That novel, which I’m now in the process of editing and laying out for publication, would not exist if not for the charity of my audience. If I choose to take out advertising on social media to sell this book — a sticky proposition at the best of times, because people get testy when they see unwanted posts and commercials in their timelines — I must be on my best behavior. The best response to a negative reaction is either a polite explanation or no response at all. It is never a vicious retort. That’s not just undignified and unprofessional; it’s the kind of thing that should get your social media page shut down. It’s the type of childish response that amateurs make. It is not the conduct of a professional who is worthy of his audience’s hard-earned cash.

Another author of my acquaintance once told a reader that he hoped the reader’s family would be viciously murdered by rabid dogs. What was the reader’s crime? He got into a political disagreement with the author on Facebook. I can’t imagine the arrogance required to insult someone who has actually spent money to read my work, even if we disagreed about something. Hell, even a bad review isn’t call to wish death on a man’s family. That’s an overreaction on a scale so absurd it sounds made up… but I watched it happen.

Self-promotion isn’t bad. You can’t survive without promoting yourself. Advertising, crowd-funding, and even some good old-fashioned e-begging are all useful tools for keeping the wolf from the door. They must always be kept in perspective, however. You must never lose sight of the fact that patronage is, on some level, charity. Yes, you are exchanging value for value — but authors are worth less than bass players in Han Dold City. Nobody with money has ever said to himself, “I need a writer? Where am I going to find one of those?”

You can’t throw a half-finished Cafe Mocha out the front door of a Starbucks without hitting at least three writers. You are replaceable — and there’s plenty of competition for you what you do. That means you can’t afford to forget your manners. The next time you take hat in hand to ask your audience to buy your latest masterpiece, remember what you’re doing. Remember that you continue to write, and to eat, because of your clients.

Be they employers or customers, everyone who pays for what you do is a client. These clients form your audience. Be worthy of your audience and they’ll show you the support you truly deserve.