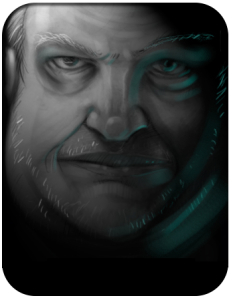

DETECTIVE MOXLEY, Part 7: “Don’t Ask”

“Tell me I should see the other guy,” said Moxley.

“Tell me I should see the other guy,” said Moxley.

Connor looked annoyed. “Huh?”

Moxley sighed. “It’s what you say, Connor. ‘You should see the other guy.’ Then you tell me he through the first punch and you put him on the floor defending yourself.”

The polished wooden bench on which the pair sat was worth more than Moxley’s car. In front of them, shadows moved on the other side of the frosted glass in the door to the Principal’s office. The conversation kept growing heated, allowing Moxley to overhear snippets of conversation before somebody shushed somebody else. The parents of the kid Connor had beat up were talking to this Rentner-Nile character. The glass in her door had her hyphenated name painted on it. Moxley hated hyphens for the same reason he hated lettuce: You didn’t need a reason to hate something pointless.

“They’re going to sue me,” said Connor. He was as convinced of his dire fate as any fifteen-year-old could be.

“Nobody’s going to sue you,” said Moxley. “His eye is swollen shut, is all. He’s got another.”

“What if I blinded him?” said Connor. “What if he comes after Mom ‘cause they have to replace his retina?”

“What if he does?” said Moxley. “You think that kid’s entire head is worth more than a hundredth of the money what’s-his-name has on and off the books?”

“Don’t talk about Mister Enoch that way, H—” The boy stopped short. He started to say something else and then gave up on it.

“Howard,” said Moxley. “I can hear you trying it on for size. You call me ‘Howard’ instead of ‘Dad’ and you and me are going to have a problem.”

Connor sulked. “Sorry,” he said. There was no apology in his tone. He stared at his feet, which drew Moxley’s eyes. The boy’s sneakers were grimy and worn.

“What happened to those air moccasins I bought you?” said Moxley. “Those hundred-twenty-chit limited editions? The ones you wanted so bad you were ready to sell your kidneys?”

“Mom,” said Connor. “She said I didn’t earn them. And that they were probably stolen.”

“I wouldn’t steal sneakers,” said Moxley.

“No,” said Connor. “Mom said you would steal the money to buy them.”

Moxley massaged the bridge of his nose with two thick fingers. “Maybe you should tell me why you tried to punch that kid’s lights out. What’s his name?”

“Jeremy,” said Connor. “Jeremy Dale.”

“So?” said Mox. “What’d he do?” He patted his pockets, looking for his pack of vapes. Connor caught the motion and gestured to the No Smoking sign next to the Principal’s door. Moxley stopped himself from swearing out loud.

“I don’t know.”

Mox squinted at Connor, turning his head to one side. “Don’t you start that crap with me,” he said. “You didn’t wake up with a brain parasite this morning, did you? No? Then you know why you did it. Out with it, Connor. You want to get this over with, we gotta get in front of it.”

“Mom says—”

“Judith’s not here,” said Mox. “And you knew that or you wouldn’t have given them my number. Why don’t you ever call me, Connor? You know she doesn’t want me buzzing you, but she wouldn’t stop you if you called me up. I tried to call you at Christmas.”

“Mister Enoch’s Vegan Orthodox,” said Connor. “They don’t celebrate Christmas.”

“That wasn’t my point and you know it. Damn it, Connor, I’m trying to help.”

“You don’t help,” said Connor. “I thought you could but you don’t. You never do.” Fat tears began to stream down his cheeks. One of them splashed on the bench next to Moxley’s leg. “I don’t know why I thought you could.”

Moxley looked up at the ceiling, squeezing his eyes shut for a moment. Finally, he looked down at Connor again. “Just tell me what happened. I’m on your side, Connor. I’ll make this go away.”

“Mom says never to believe you if you promise something.”

Moxley opened his mouth, then closed it. He turned away. Standing, he walked to the end of the little anteroom, which boasted a pressure-sealed window. On the grounds outside, robots worked the landscaping. Mox found himself wondering if any of them might be Ogs in disguise.

The door to the Principal’s office opened. A child with a very puffy left eye — Connor was right-handed — was ushered out, his parents on his flanks. They made a show of not looking at Moxley as they passed. The kid, for his part, looked pale and fragile. He looked, and when Moxley caught his gaze, he almost recoiled. Jeremy Dale’s right eye was so bloodshot it looked like he’d popped a vessel. No wonder Connor was worried about retinal detachments.

When Dale and his parents had gone, Moxley gestured for Connor to enter. The Principal, however, shook her head. “I’d prefer to speak to you alone, Mister Moxley,” she said. “Connor, please wait outside for us. Your father will take you home when I’ve finished speaking with him.”

“Okay,” said Connor, looking once more at his feet.

Rentner-Nile closed the door and sat down behind her desk. She did not invite Moxley to sit. He picked one of the ornate wooden chairs available and eased himself into it. Rentner-Nile looked on with disapproval. Didn’t want him on the furniture, he figured.

“I’ve spoken with the Dales,” said Rentner-Nile. “They are willing to consider the matter closed if Connor is appropriately punished. I am doing him the courtesy of giving him two week’s in-school suspension.”

“You don’t maybe want to figure out why he did it?” Moxley said. “Is this Dale kid a bully?”

“Hardly,” said Rentner-Nile. “Neither boy has been a discipline problem previously, although I am not at liberty to discuss the records of a child who is not yours. Frankly, Mister Moxley, I’m surprised you were able to come. It was my understanding that you are… not a presence in your son’s life.”

Moxley felt his molars grind. “Not my choice,” he said quietly. “Connor’s mother and I are divorced. She has full custody.”

“Did he say why he hit Jeremy?” asked the Principal. “Neither boy was willing to share the story with me.”

“We’re even on that, then,” said Mox. “He won’t spill it.”

Rentner-Nile frowned. It was the face of someone who’s just found a bug at the bottom of her glass. “You have the option of an administrative review,” she said. “But I wouldn’t bother. We have a very clear zero-tolerance policy.”

“Connor stays in school?” he asked. “The other family’s going to let this be?”

“He will be punished, as I said.” The woman nodded. “But I don’t think, given his record, that we need do more. I see no justification for expulsion as long as Connor does not assault anyone else.”

“You’re keeping that a secret, right?”

“I’m sorry?” she said.

“You know how kids are,” said Mox. “You let it get out that he’s on a short leash, the other kids are going to start messing with him because he can’t fight back without getting expelled.”

“How we choose to handle disciplinary measures, Mister Moxley, is a covered in your son’s education contract. Of course, as I recall, you aren’t party to that contract, which is paid for by Connor’s stepfather.”

Moxley stared at her long enough to make her fidget. There it is, he thought. Finally, he said, “Yeah. Yeah, that’s true. I don’t have much say in this.”

“Then I suggest you take Connor home.”

“I’ll do that,” said Moxley. He pushed himself up from the chair and gathered his coat around him. He watched the woman’s eyes fall on the bloody stain over his shoulder. “Hey, just an idea,” he said. “Maybe you get a little flag, and one of those paint wands. Then you can write, ‘I’m disgusted’ on it. You could wave that around. Be a little less ambiguous, but not much.” She was opening her mouth to reply when he wrenched open the door and slammed it behind him.

“What—“ Connor started to say.

“Come on,” said Moxley. “I’m taking you home.”

“What happened?” Connor asked, hurrying to keep up with Moxley as the man huffed down the corridor. “Why is she yelling?”

“Don’t ask,” said Moxley.